Posted on April 26, 2019

Historical Context: the deQuettevilles’ Viking Roots

Posted on April 27, 2019 by Craig Cameron deQuetteville

How Many Ketils?

In posing the question of whether deQuettevilles were somewhat indigenous to Jersey, we have to consider how far back we would like to go in time for them to qualify. Would one have to have a genetic link to the Unelli, Roman, Breton or Frankish people, or would a Viking immigrant meet the requirements? (Such questions miss the mark, since there is probably a mixture of all these ethnicities in any one individual hailing from the region.)

Accounting for the origins of Ketil poses several problems. In the Cotentin peninsula of Normandy today (concentrated mostly around the Val de Saire and St Sauveur le Vicomte), there are several branches of families with the surname Quétel or Quetil, not to mention some later variants such as Anquetil and Thorketil. Though there is no place name in the region that they are named after, somewhere along the line, these people adopted the name Ketil as their surname.

On the other hand, there are over 50 place-names in Scotland and England that include a reference to someone named Ketil. In Normandy there are another 10. There are none in Ireland or Scandinavia (this needs further research). Ketil was a common name for centuries among Norwegians, Danes and Swedes, though it seems to have had an origin in Norwegian mythology. This fact alone argues for the possibility that Ketil-named settlements or geographical features are derived from many different Viking chieftains named Ketil. As we will see, there are only two Ketils who figure among the famous Vikings, those about whom stories were told. Given how many places are named after Ketil, we might ask how it can be that he was not more famous?

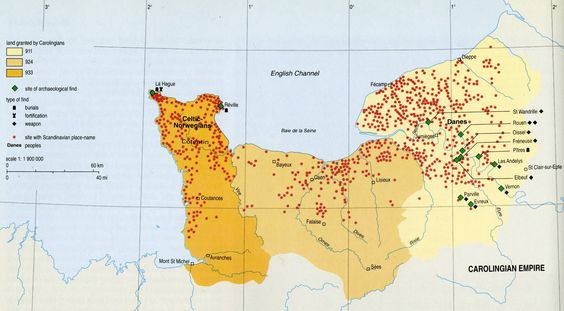

Furthermore, the range of years in which farms were settled and named can be anywhere from 790 to 1030 CE. How could one Viking named Ketil have given his name to so many places? Was there a Ketil clan whose prominent members continued to bear the name Ketil, like the Ui Niéll of Ireland, or to plant it in various settlements to which their master laid claim? Moreover, was there a separate Ketil who settled in Calvados and perhaps parts of the Cotentin peninsula as a Danish Viking who came to Normandy after years of raiding and settling in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria? Was he independent of the Hiberno-Norse Vikings who came to Normandy earlier by way of Scotland, Ireland and Cornwall? The answers to these questions should shed some light on the possible conditions for settlement in Normandy that led to the establishment of the deQuetteville family some three, four or five generations later.

A Unified Ketil Theory ?

So what do we know about Ketil? There is a passing similarity to the Latin name, Catullus, as in the famous poet, but any linkage is difficult to establish. In addition, ‘Ketil’ bears a resemblance to the name of a Celtic tribe, the Catuvellauni, which originated somewhere in Belgium and Northern France, but which was well settled in southwest England at the time the Romans arrived. Yet, neither of these explanations can tell the full story.

In a Norse context, the name, or nickname, “Ketil”, comes from the Old Norse, Old Germanic word for ‘pot’, ‘cauldron’ or ‘chalice’. It is thought that a metal pot could be worn as a helmet, so some have taken it to mean that a person with this nickname was a ‘hersir’ or war-lord; the point being that only a man of wealth could afford such objects of iron to be used in warfare. Others believe it to have been related to a ceremonial role, such as a cup-bearer. The ‘cauldron’ may have had religious significance in that it contained sacrificial blood as part of ritual ceremony. (One of the sagas tells of how Thor stole a ‘cauldron’ from a giant. Such cauldrons were used in the making of beer and mead.) By the 10th century ‘Ketil’ in Norway, ‘Ketel’ in Denmark and ‘Ketel ‘ in Sweden is a popular name, one that appears on runestones in Scandinavia, though by this time bi-thematic variants, such as ‘Osketil’ and ‘Thorketil’, occur more frequently in Denmark and Sweden.

As far back as the 8th century, Ketel is a mythical figure, akin to Odysseus. He is born in Hrafnista, (present-day Ramsta in Halogaland), along the northern coast of Norway. His legend is recalled in the Hrafnistumannasögur[i] where he is depicted as an ‘askeladden’ who outfights or outwits trolls, dragons and giants in order to save a princess. Ketel’s daughter Hrafnhilda, who marries Thorkel of Namdalen, bears a son named Ketil Thorkelsson[ii].

This Ketil, who also goes by the name Ketill Haengr, or Ketil Trout, will go on to become one of the early settlers of Iceland, where he fled after having fought against King Olaf I of Norway. His descendants on Iceland will recall the events of Ketill’s life in various sagas, most famously the Landnamabok. From some point in the 750s, Norwegian settler-warriors had begun to colonize the Faroe, Shetland and Orkney islands and the Outer Hebrides.

By 795, raiding of monasteries had begun, such as at Inisbofin and Inismurray in Ireland and St Columba in Iona or on Skye in the Inner Hebrides. Danish pagans saw how pagan Saxons had been treated by Christian Franks when in 778 Charlemagne had had 4000 Saxon warriors decapitated. This forced many Saxon families to take refuge in Denmark where their stories of genocide spread across Scandinavia. The event may have been the catalyst for the Vikings to plunder Christian houses of worship and take Christian slaves. The Viking Age had begun.

The Man vs. the Myth

Apparently, Ketil Haengr is a different character from the historical Ketil Flatnefr (“Flatnose’), though their stories have some elements in common. Depending on which saga one reads, Ketill Flatnefr becomes King of the Hebrides sometime in the 9th century after a dispute with the King of Norway. This Ketil has some potential significance for understanding how the Norwegian-Hebridean Ketil came to Normandy as the result of political events in the territories on either side of the Irish Sea. On one hand, it is conceivable that our Ketil was among the Danish Vikings who later arrived in Normandy as settlers after being evicted from Northumbria in the 890s. On the other hand, it seems more likely that he was among the Norse-Gaels who arrived in the Cotentin peninsula as a group, separately from other Scandinavian Vikings.

Andrew Jennings and Arne Kruse make a convincing argument that Ketil Flatnefr and Caitill Find are legendary variants of the same historical person[iii]. Based on an onomastic analysis of Norse settlement patterns in the Hebrides, they hypothesize that the ancient Pictish kingdom of Dall Riata comes under the control of Norse invaders beginning as early as the 820s, eventually becoming the kingdom of the Gall Gaidall, the name given the Norse-Gael people who emerged later in the 9th century around what is today Galloway.

Ketil Flatnefr was a Norse ‘hersir’ or jarl based in the Orkney Islands as detailed in the Orkneyinga saga. Indeed, there is still a place name on the isle of Sanday in the Orkneys called Kettletoft, or Ketil + farm. (We will see another Ketel-toft in Normandy, now caled Quettetot.) The Orkneys, and the Shetland Islands before them, had been settled from sometime in the 750s and its Pictish population either subsumed, exported into slavery or killed. One potential origin for the name Ketil, also pronounced Caitil, is the Pictish name for the Orkney Islands and the people inhabiting them, the Cat. We see this reflected in the name for the northernmost portion of Scotland, Caithness.

A settlement pattern based on violence would later repeat itself as Ketil Flatnefr-Find conquered the Outer Hebrides, but his eventual conquest of the Inner Hebrides is different. There, he seems to come to some compromise with the local Christian Picto-Celts, until the two groups co-habit peacefully and the Norse merge with the locals while maintaining control. Presumably, by this time at least some of the Norwegians had learned to speak the local languages and would use this ability to their strategic advantage. Such a gradual assimilation is closer to what happens in Normandy.

Caitill Find is a reputed, if not self-proclaimed, King of the Gall Gaidall — the fair foreigners, as they were called by the Irish — the second and third-generation Hebridean Vikings. His daughter, Audr the Deep-Minded, will marry the Norse King of Dublin, Olaf the White (Amlaib in Old Irish), in 853. (Archaeological evidence for Viking settlement in Inner Hebrides — in particular the discovery of a Viking thing site in the purported capital on the isle of Bute — might reveal interesting parallels to that in Normandy, such as Le Tingland near Cap de la Hague (see Riddel), or on the Channel Islands). Ketil and his wife, Yngvilder Ketillsdottir, daughter of Ketil Werther, a jarl from Romirike, Norway, had several children; including Bjorn Ausmadr Ketilsson, Helgi Bjolan, Audr the Deep-Minded, Thorunn Hyrna and Jorunn, mother of Ketil the Fisherman, who colonized Kirkjubar in Iceland.

Audr’s story is interesting in itself. It may also provide clues to Ketil’s identity. If Audr is a young bride of 15 or 16 when she marries Olaf the White, she must have been born in about 838. Audr and Olaf had four sons, Thorstein the Red, Oystein, Carlus and Halvdan and a daughter Jocunda. Audr leaves Olaf, who had had a falling out with Caitill in about 859, and flees to Caithness. There is some speculation that the falling out occurred because Olaf took a new wife, perhaps an Irish or Norwegian princess. Thorstein is killed in about 871 and she hears news of her father Ketil’s death in Scotland around the same time. Audr builds a large ship and sets out for the Orkneys, then the Faroes and eventually Iceland (which had been discovered by Floki in 815) around 871 (or 895 according to the Laxdala saga) where she is one of the first settlers and the first Christian settler, having converted probably sometime during her time in the Hebrides near the monastery of St Columba on Iona. Jennings and Kruse demonstrate how several freed men and slaves who Audr takes with her to Iceland were of Celtic and probably Hebridean origin.

Interestingly, Dr. Cat Jarman has recently hypothesized that a Viking warrior buried at Repton alongside his son is Olaf the White and Oystein. Both men were killed violently, probably in battle. It is speculated that they were killed in Scotland and that their bodies were transported to the church at Repton, the capital of the Kingdom of Mercia, in a show of dominance on the part of the Great Heathen Army wintering nearby. Dr. Jarman and her colleagues give 872 as the year that this happened. Could this event be the source of the Irish Annals’ confusion over the purported death of Ketil? If the warrior’s son is indeed Oystein, or any one of Audr’s sons, might it be possible to establish a DNA link between him and descendants of Audr living in Iceland today or of Ketil living in Normandy?

Indeed, the Landnamabok sagas relate a genealogy for Ketil Flatnefr that adds strong evidence that this Ketil was the founder of the settlements in Normandy named after him. An entry in the Geni website database of genealogical information provides the following:

Ketil, nicknamed Flatnose, was a Norwegian hersir of the mid 800s, son of Bjorn (or Bjarni) Buna. His holdings were in the northern part of the country. Some scholars have speculated that, based on his location, nickname and his father’s non-Norse cognomen, Ketil was at least partially Sami in descent.

In the 850s Ketil was a prominent viking chieftain. He conquered the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. Some sources refer to him as “King of the Sudreys” but there is little evidence that he himself claimed that title. The Norwegian king appointed him the ruler of these islands, but he failed to pay tribute to Harald Fairhair and was outlawed. Most of his family eventually emigrated to Iceland.

Ketil’s wife was Yngvild Ketilsdattir, daughter of Ketil Wether, a hersir from Ringarike. They had a number of children, including Bjorn the Easterner, Helgi Bjola; Aud the Deep-Minded, and Thorunn the Horned.

Ketil’s daughter Aud married Olaf the White, King of Dublin. Their son, Thorstein the Red, briefly conquered much of northern Scotland during the 870s and 880s before he was killed in battle. Aud and many members of her clan settled in the Laxdael region of Iceland.

Ketil may have been the Caittil Find, who appears in Irish sources, in 857, as a leader of a contingent of Gall-Gaedhil.

https://www.geni.com/people/Ketill-Bjarnarson-King-of-Mann-and-the-Isles/6000000001169157385

As previously discussed, deQuettevilles living today who have undergone DNA analysis also show markers of a haplogroup indicating some Sami-Finnish ancestry. But perhaps more germane is the family tree attributed to Bjarn ‘Buna’ Grimmson, Ketil’s father. Ketil son of Bjarn son of Grim is said to have had two brothers, Hrappur Bjarnson and Helgi ‘Bunu’ Bjarnson. (Also note that the names of two of Ketil’s sons are Bjarn and Helgi Bjolan.) Helgi Bunu would go on to settle in Iceland and his kin wold provide a base of support for the arrival of Audr and her retinue.

But before he did so, Helgi must have been active in Normandy and Britain along with Ketil. We will see in “The Viking Years: Part II” that at least two settlements in La Manche, Normandy, that are named after Helgi are in close proximity to settlements named after Ketil. Accordingly, any correspondent chronology would have Ketil and Helgi forming settlements in Normandy and Britain in the 850s and 860s, with Helgi eventually travelling to Iceland in the late 870s, to be followed by Audr in the 890s.

In fact, among Ketil’s Gall Gaidhall contingent of Hebridean-Norse Viking mercenaries that was known for their ferocity were several key family members and associates. In addition to Ketil’s brother, Helgi, there was Ketil’s son, Helgi, and a son-in-law, Helgi “Magri’ Eyvindarson, husband of Thorunn. Also, Ketil’s father Bjarn may have accompanied him at one point, but surely Ketil’s son, Bjarn, did as well. Ketil’s father-in-law, Ketil vaeder Vaer, Jarl of Ringerike, may have taken part in raids with Ketil, too.

Ketil’s son, Helgi, had a wife, Thorny Ingolfsdattir, whose father was named Ingolfr. He may be the Ingolfr who gave his name to Inthéville in La Manche. Then there are Olaf and Audr’s sons, Thorstein and Oystein, who also may have given their names to settlements in La Manche and elsewhere in Normandy. And this list should include Dicuil, Neil, Farmar and Morfar whose names are clearly of Picto-Celtic origin, along with several others. That many of Ketil’s family eventually settled in Iceland should not detract from the possibility that they spent some time in Normandy, as it is possible that those who emigrated to Iceland were sympathetic to Christianity and found there a more hospitable environment to practice their new faith.

That the Irish Annals recount how Caitill Find died while fighting in Scotland, without giving details, is our only record of how Ketil might have met his end. It may be, however, that this was based on speculation or error, as it is the same fate met by Ketil’s grandson, Thorstein the Red. Likewise, although the sagas tell of many of Ketil’s kinsmen having settled in Iceland, there is no indication that Ketil ‘Flatnefr’ Bjarnarson did so.

Ketil may have relinquished his Hebridean territories to the control of Olaf and subsequently found greener pastures in Francia. It is known that Olaf the White and his associate Ivar the Boneless sailed to as far as the coast of Spain in the 850s and mixed with the Vikings overwintering on Noirmoutier. Would it not be likely then that Ketil had travelled in similar circles when he was allied with his son-in-law, Olaf? A lucrative trade in wine and slaves had developed on the wine-route stretching from the north of Spain along the coast of France and up into the Irish Sea. While Ketil is said to have lost control of the Irish Sea route to Olaf by 859, it is possible that he continued ‘aviking’ together with the Scandinavians in the English Channel and around the Seine and the Loire.

As we know that the town of Coutances was raided and burned in 866, for example, it could be that Ketil was among the raiders who carried out the attack and that the settlement at Quettreville-sur-Sienne was founded at this time. This is around the time that Hastein (Hasting), who is also associated with Olaf the White and Ivar[i], was prominent in the Loire and Seine area, as well as on the Channel Islands, according to Wace. Quettreville is in the middle of a cluster of Viking settlements south of Coutances.

It is situated on what is today “route departementale D971” that runs from Coutances to Bréhal to Granville on the coast and which probably lies in part on an ancient Roman road. Nearby, the river Sienne would have given the Vikings a water route for quick access to the sea for their shallow-bottomed boats. Were these settlements established as a defensive bulwark against Breton incursions from the south? Or, perhaps in conjunction with Breton locals? The location provided close proximity to the Channel Islands, which may have acted both as a spring-board for attack and a refuge for escape from their enemies.

Ketil/Caitill and Richer’s Ketil

Further evidence for the presence of a Viking named Ketil in the area of West Francia comes from Richer of Rheims. I will venture one area of investigation hypothesizing that Richer’s Ketil and the Hebridean Ketil Flatnefr (Caitill Find) are plausibly one and the same. Writing in the late 10th century, 100 years after the events, Richer describes how the Ketil (ca. 815-887) of his Histoire was one of the leaders of the Great Army of Danish and Norwegian Vikings who sailed up the Seine and laid siege to Paris from November of 885 to May of 886. Ketil had been among the Vikings who had raided in Brittany and up the Loire River.

In Richer’s account, Ketil is a warrior commanding 60 or 70 ships (probably an exaggeration) out of a total of 700 at the time he participates in the attack on Paris, whose main leaders were Siegfried (Sygtric) and Rollo (Hralfr). Several heroic deeds are attributed to Ketil during the siege, including the idea for building a defensive earthworks and pitfalls against the Francian cavalry. But Richer also describes how a year or so later Ketil was captured by Count Hugh of Paris after a battle near Limoges. Ketil agrees to convert to Christianity to save his life, but at the baptism ceremony in front of the altar he is run through with the spear of Ingo, a mid-level Francian who had helped to win the battle for the Franks. While a strange story, it may actually be accurate in terms of the relative time of Ketil’s death.

Richer also claims that Ketil was the father of Rollo. David Crouch gives credence to this claim, based on the fact that it is nearer in time than those claims that are made from the Icelandic sagas that Rollo was the son of Jarl Rognevald from Romike. While Ketil may not have been Rollo’s biological father, he was more likely to have been a mentor in war and a guide for Rollo, who is believed to have passed time in the Hebrides before arriving in Francia. As it is believed by both historians that Rollo had some connection to the Hebridean-Norse raiders, it solidifies the conjecture that Ketil was also among them. Furthermore, it is mentioned by Richer that Rollo participated in the 885 siege of Paris, as well. Afterward Rollo retreated to the Val-de-Saire in the Cotentin, wintering at St-Vaast near what today is Quettehou, from where he may have participated in a siege of St Lô in 889 (sources).

There may be some veracity in this scenario. When the settlement patterns and naming patterns of Normandy are compared with those of the Hebrides, as elucidated by Jennings and Kruse, a significantly different historical arc emerges than what is generally believed. I will try to flesh out this thesis more thoroughly in an upcoming page entitled “The Norman Years I”. For example, while it is known from historical accounts and archaeological evidence that Vikings first wintered on Noirmoutier Island near the mouth of the Loire in 842, on the Isles of Sheppey and Thanet at the mouth of the Thames in 852, and on Oissel and Jeufosse on the Seine from 845 onward, it may also be that they did so on Jersey and Guernsey in the late 830s or early 840s.

Caitill/Ketil on the Channel Islands?

Islands, particularly small ones with arable land, were ideal for housing and feeding slaves who had been captured on the mainland until they could be transported to the slave markets of Rouen, Dublin and Hedeby. A memory from this time may have lingered 200 years later when in a charter relegating two Jersey churches to the Abbey of Cerisy by William the Bastard in 1042 mention is made of one of them as the church of St Mary of the Burnt Monastery.

Many commentators note that Jersey is probably named after a Viking named Geirr, with the suffix ‘-ey’ being Old Norse for ‘island’; and that Guernsey is probably named in the same fashion after a Viking named Garin, or Warinn[iv]. (Others have noted a possible link to the river Gerfleur that empties into the sea at Barneville-Carteret[v].) (According to the Jersey poet Wace, the monastery of St Magloire on Sark was destroyed sometime in the 850s by the Danish Viking Hasting (Hastein). Sometime afterward, the monks of Guernsey were forced to remove their relics to Dol in the 850s to prevent further Viking plundering).

It has not been noted, to my knowledge, that there are parallels to the name of Jersey in the name of the island of Gairsay in the Orkneys (= Gareks + ey, or Giers + ey) and also the island of Dursey, Co. Kerry, off the southwest coast of Ireland (Kerry was attacked by Vikings in 812; the monastery on island of Skellig Michael, near Dursey, was raided in 823). Off the south-western tip of Cornwall in Sennen, Penzance there is a tiny islet with a lighthouse called Kettle’s Bottom. Not far from there is a promontory on Old Grimsby, one of the Scilly Islands, named Kettle Point.

Additionally, off the east coast of Guernsey lies the islet of Jethou, which is referred to in a charter of William the Bastard dating between 1027-35 as Keitelhulm, or Ketil’s Islet (there is also a Ketelhulm in Yorkshire). These are fairly unique occurrences of the phenomenon of Viking place-names that persisted for geographical entities other than farm names, at least in the Channel Islands. (It should also be mentioned that there was a large sandbar, or islet, on the Seine called l’Ile de Cativelle in the commune of Freneuse.[vi] Not clear if this is derived from Ketil or Cati.) The naming of these islands after individuals does not necessarily denote a form of ownership. Rather, it might simply be a result of the first Viking hersir who camped there. And it has been well established how important the naming of geographical features was for navigating sea routes.

In line with the analysis of Jennings and Kruse, these geographical features would also have to have figured as some of the earliest examples of Viking naming in or round the Channel Islands, perhaps dating to the 840s or slightly before. Following some indices from GIC — viewing in Google maps, for instance, the approach to the Channel Islands from the north-west that people sailing from the south-west of England would have taken — we see that Jethou, Guernsey then Jersey would have served well for island-hopping purposes, where the Vikings rested and held their loot and slaves from vengeful locals on the mainland. It may well be that one or more of the smaller island were for a time depopulated of local inhabitants who were enslaved or who fled as refugees, though this claim is unverifiable. It may equally be the case that there was relatively peaceful co-existence between Gael-Gaidall settler-raiders and Breton locals on Jersey and Guernsey, as they would have partially understood each other’s common Brythonnic language.

That the Vikings did not settle permanently on Jersey and Guernsey, or were quickly assimilated, may explain the dearth of Norse place-names there compared to the shoreline along the northern coast of the Cotentin, where settlement rapidly took root in numbers that would not have been ideal on an island the size of Jersey. (Archaeological activity should be focused on searching for further evidence to support this claim).

From the Channel Islands and the Cotentin, the Loire and Seine Vikings had easy access to both river basins and to England. There was plentiful supplies of ash and oak timber, and iron for nails, to build ships, as well as access to flax for making sails. Some of the slaves that the Vikings captured, or locals who submitted, would have been used to work the farms for food supplies. All this provided an excellent platform for raiding north and south along the coastal waterways. By 867, one year after the burning of Coutances, the West Francian King, Charles the Bald, had given his vassal, King Saloman of Brittany, control over the Cotentin and the Channel Islands as a way of countering the growing Viking presence. Clearly, the Viking settlement of the Cotentin was well underway.

For the purposes of determining a chronology for the relationship between Ketil and Quetteville, it must be surmised from Jennings and Kruse’s work that Keitelhulm, now Jethou, is the earliest of the Ketil-related place-names to have been assigned in Frankish territory. This points toward an interpretation of events whereby Guernsey, and probably Jersey, were over-wintering grounds for Hebridean-Norse Vikings 5 or 10 years before any actual settlement took place in the Cotentin sometime later in the 850s or 860s. Gradually, farms were established on the mainland and named after other Hebridean-Hiberno-Norsemen, with names such as Dicuil, Neil and Duncan, whose farms eventually became Digulleville in La Hague and Néville-sur-mer, Nehou and La Rue Doncanville near Quettehou, respectively[vii].

In the Hebrides during the pre-Norse Dal Riadan kingdom, communities were organized into ‘vingtaines’, or ‘twenties’, a grouping of 20 houses whose inhabitants could furnish enough rowers (about 28 men) to man a Dal Riatan warship[viii]. This practice must have been adopted by the Hebridean Vikings and then transplanted in the Channel Islands. On Jersey, 10 of the 12 parishes are organized into four or five vingtaines each. In St Martin parish, for example, there are five; Vingtaine de Faldouet, Vingtaine de Fief de la Reine, Vingtaine de Rozel, Vingtaine de la Quérée and Vingtaine de l’Église. This, of course, pre-supposes a commensurate population base.

Some archaeological evidence also exists to support the fact that Vikings lived for a while in the Channel Islands; for instance, a Roman stone column was found at St Lawrence parish church that had been reworked on one side in Celto-Norse strap carving. (Note: this is not far from the fief es Houndois, which may be name after the 9th-century Viking, Hundeis.) As we will see that a fief es quetivels later existed in St Lawrence Valley, one is tempted to draw a line between the two. All this leads to a hypothesis that the Ketil clan may have maintained a homestead on Jersey from this time.

A French source postulates that the name of the fief, ‘Quetivel’, that is today associated with the mill in St Peter parish, derives from the anthroponym Ketil + -välr, which is Old Norse plural for fields, or meadows. That Quetivel Mill lies in a valley complicates this interpretation. However, there may a slip that occurred between –välr and –dälr, which is Old Norse for valley, or dale, and which appears as a suffix in several place-names in Scandinavia and the British Isles. Could this be a sign of continual habitation on Jersey of members of the Ketil clan from the 9th century as far as into the 13th century? It is a question that needs exploring.

[i] (http://www.germanicmythology.com/FORNALDARSAGAS/KetilsSagaChappell.html)

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ketils_saga_h%C5%93ngs)

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ketil_Trout_(Iceland)

[iii] Jennings, Andrew and Kruse, Arne. “From Dal Riata to the Gall-Gaidheill”, Viking and Medieval Scandinavia. 5. Brepols. https://www.academia.edu/237929/From_Dalriata_to_Gall-Gaidheil

[iv] https://www.theislandwiki.org/index.php/The_origin_of_the_name_Jersey

[v] Vikings At War; Hjerder Kim and Vike, Vegard. Casemate Publishers. Oxford. 2016.

[vi] https://www.wikimanche.fr/Gerfleur;

[vi] http://cths.fr/dico-topo/affiche-vedettes.php?cdep=76&cpage=532

[viii] https://books.google.ca/books?id=U-2vCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA81&lpg=PA81&dq=viking+anthroponyms+in+England&source=bl&ots=BxN-h0l9dz&sig=mjtkrQ5BH6pjeqIYI9it91GZHw4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwir-q356pXfAhXNqYMKHflJDIgQ6AEwE3oECAIQAQ#v=onepage&q=viking%20anthroponyms%20in%20England&f=false

ix Ridel, Elisabeth. “The Celtic Sea-Route of the Vikings”. In….

[viiix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A1l_Riata; see also Duffy, Seán. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2005. p.586

Generally I do not read post on blogs, but I wish to say

that this write-up very compelled me to take a look at and do it!

Your writing style has been surprised me. Thank you, very great article.

LikeLike